Return to mylesstandish.info Return to - the Ancient Parish of Standish

Links Charnock City India. Stephen Charnock, (1628–1680) Residents of the Manor of Charnock Richard in 1588. People and events in Charnock Richard 1199 to 1804

![]()

The Charnock Family: from the Manor of Charnock Richard to Charnock City India.

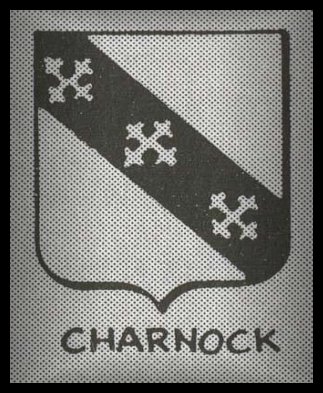

Charnock. Argent on a bend sable three crosslets of the field

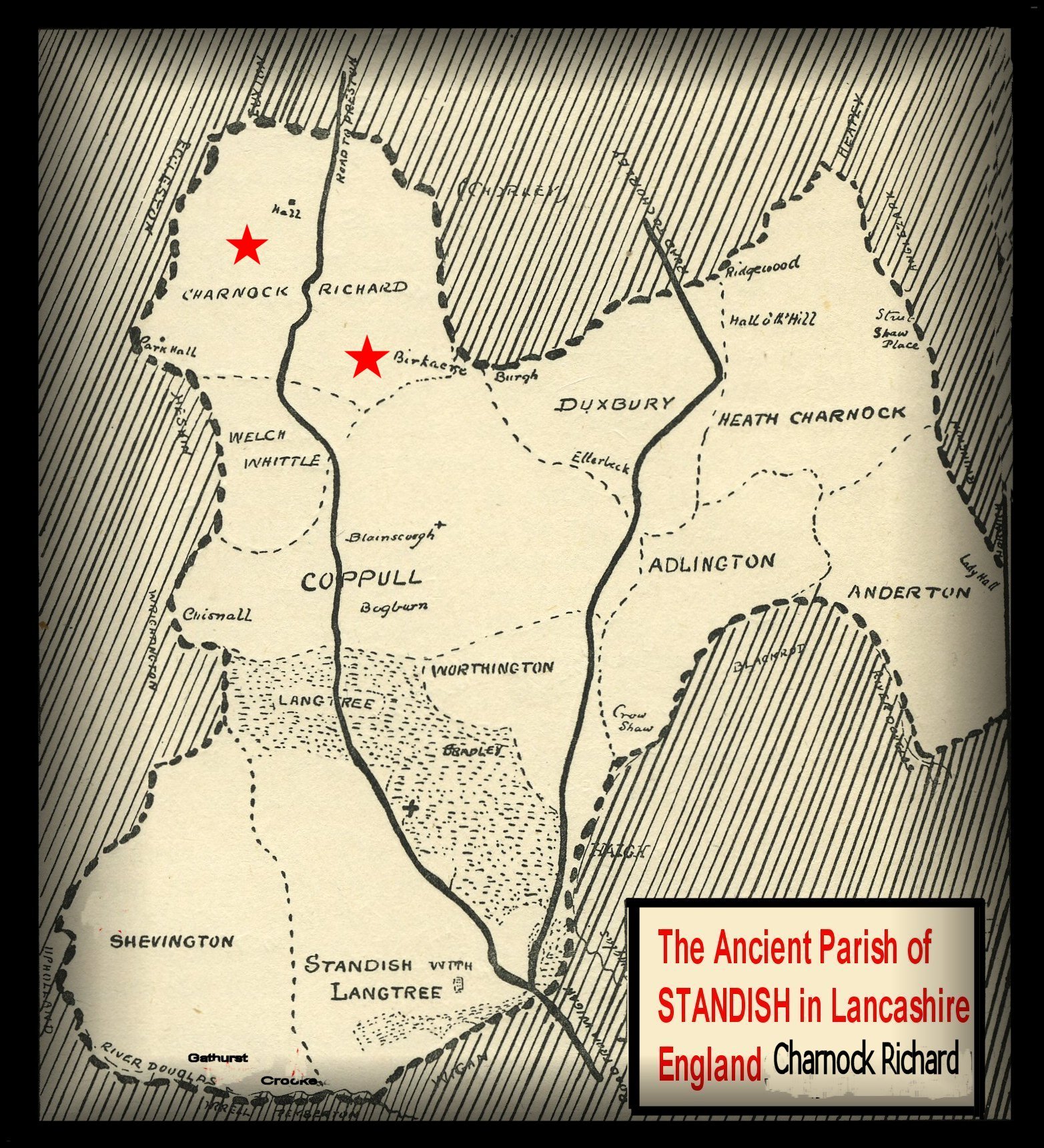

The Manor of Charnock Richard within the -

Ancient Parish of Standish Lancashire England.

Schernoc, 1288; Chernok Richard, Chernoke, 1292.

This township is bounded on the east and north by the Yarrow; Clancutt Brook on the south divides it from Coppull. The surface reaches heights of 250 ft. or more in several places near the centre, descending somewhat rapidly to the Yarrow.

In 1666 the only house of any size was that of John Hoghton, with

twelve hearths; the township had eighty-seven hearths chargeable with the tax.

(fn. 3)

The whole of CHARNOCK RICHARD was within the barony of

Penwortham, and was by Warine Bussell given with other manors to Randle son of

Roger de Marsey, (fn. 4) and it was therefore held in later times

'of the lords of Leylandshire.' A moiety was, with Shevington and Welch

Whittle, granted before 1242 as the fourth part of a knight's fee, held in the

year named by the heir of Robert Banastre. (fn. 5)

The Charnock part of this estate was soon afterwards given by William Banastre

to Henry de Lea (fn. 6) ; while the moiety not included in it was

held by a family which assumed the local surname and in return gave it the

distinguishing epithet of Richard. (fn. 7)

Hence in 1288 Henry de Lea and Henry de Charnock each held a moiety of William

de Ferrers by rents of 5s. and 2s. respectively. (fn. 8)

Henry de Lea in 1284 obtained a royal charter for a market every

Friday at his manor of Charnock, and an annual fair on the eve, day and morrow

of St. Nicholas; also free warren in his demesne lands. (fn. 9)

The market and fair do not seem to have prospered, but the grant of free warren

led to the formation of a park, (fn. 10) and the distinguishing name of the Park or

Park Hall (fn. 11) for that share of the manor. Like the

other Lea manors, it descended to the Hoghtons of Hoghton Tower, (fn. 12)

and in 1606 was acquired by Richard Hoghton, an illegitimate son of a former

Sir Richard, who had probably settled him there at first. (fn. 13)

Richard Hoghton of Park Hall died in 1622 holding the moiety of the manor of

Charnock Richard, with various lands, water-mill, dovecote, &c., of Richard

Shireburne and Edward Rigby, by the ancient rent of 5s.; also other

lands in Welch Whittle, Heskin, Chorley, Euxton and Lancaster. Richard's son Alexander

had died before his father, leaving a daughter Anne, twenty-eight years of age,

and wife of Thomas Bradley; but Park Hall descended to Richard's younger son

William. (fn. 14)

Park Hall

This branch of the family adhered to the Roman Catholic faith, (fn. 15)

and William Hoghton zealously espoused the king's cause on the outbreak of the

Civil War. He was made a lieutenant-colonel, but fell at the first battle of

Newbury in 1643. (fn. 16) The estates were at once sequestered by

the Parliament, and in 1652 John, William's son and heir, petitioned for an

allowance from his inheritance, as he was 'in no way guilty of delinquency, but

was a recusant.' (fn. 17) The estates were, however, sold under the

third Confiscation Act of 1652, (fn. 18) but in some way regained. John Hoghton

recorded a pedigree in 1664, (fn. 19) and his son William, born in 1659, married

the daughter and ultimate heir of Robert Dalton of Thurnham. Their son John

took the name and arms of Dalton about 1710, and his descendants have retained

possession of Thurnham. (fn. 20) Park Hall, however, was sold by the

Daltons in the latter part of the 18th century (fn. 21)

; in a recovery of 1787 William Jeffreys was tenant of the moiety of the manor

of Charnock Richard, with messuages and lands there and in Leyland. (fn. 22)

Richard Prescott German was owner in 1836, (fn. 23)

Mrs. Alison in 1869 (fn. 24) and Mr. Henry Alison, great-grandson of

the purchaser in 1789, was the owner and reputed lord of the manor. No

courts were held, but a number of chief rents were payable. (fn. 25)

Of the other and possibly superior moiety of the manor but little

can be said. Richard de Charnock, who appears in 1242, (fn. 26)

had before 1284 been succeeded by Henry son of Thomas de Charnock, (fn. 27)

and in 1292 William de Lea and Henry de Charnock were lords of the vill. (fn. 28)

In 1304 Adam son of Henry de Charnock was espoused to Joan daughter of Richard

de Molyneux of Little Crosby and Speke, (fn. 29)

and lands in the latter township remained in the family for some generations.

Adam was succeeded by his son Henry, living as late as 1370, who in 1366

granted his lands in Speke to his son William and Margaret his wife. (fn. 30)

The succession for some time is uncertain, but in 1427–8 Richard de Hoghton and

Henry de Charnock were lords of Charnock. (fn. 31)

The next to appear is Robert Charnock, living in 1491 and 1498, (fn. 32)

and soon afterwards succeeded by his son William, whose son and heir was Henry.

(fn. 33)

Henry Charnock died in 1534 holding the moiety of the manor of

Charnock Richard of the Earl of Derby, Lord Mounteagle, and Richard Shireburne

in socage by a rent of 2s. 1d.; also lands in Chorley, Speke,

Hindley and Much Woolton. The heir was his grandson Thomas, son of Robert

Charnock, seventeen years of age. (fn. 34)

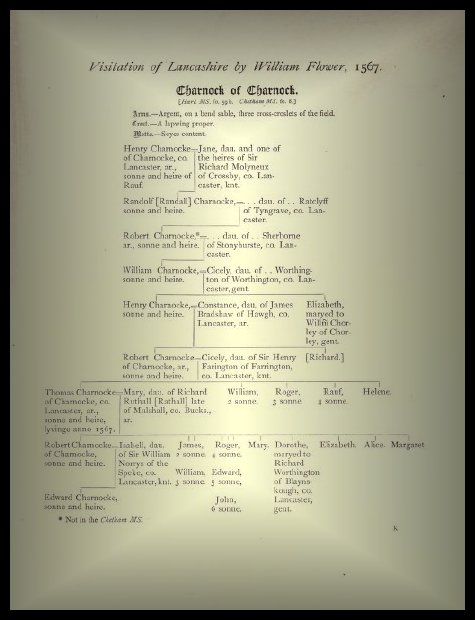

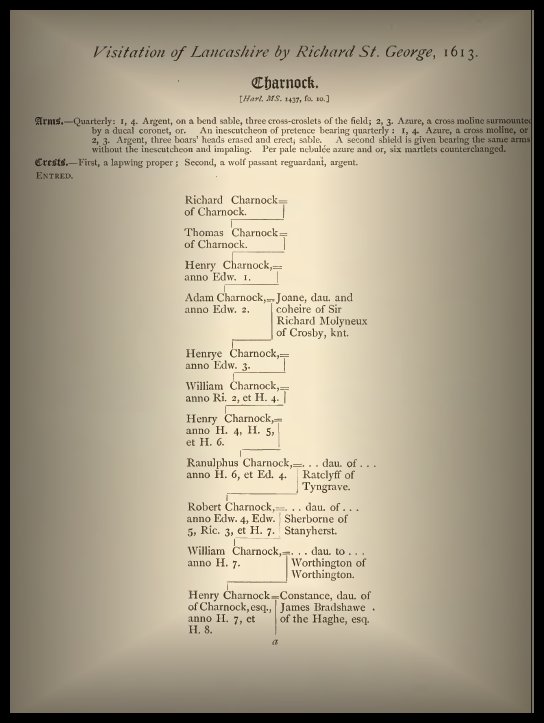

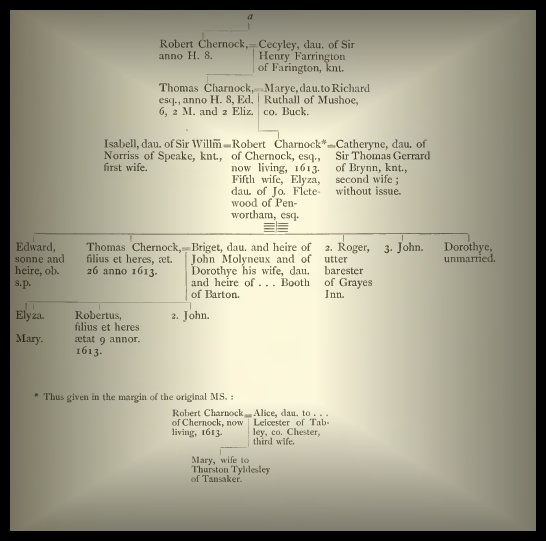

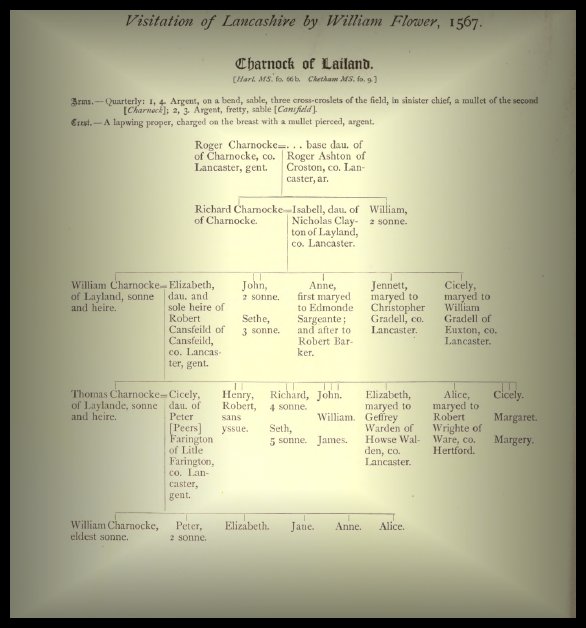

A pedigree was recorded in 1567. (fn. 35)

Thomas Charnock died in 1571 holding the moiety of the manor and other lands,

and leaving a son and heir Robert, thirty years old. (fn 36)

John Charnock, a younger son of Thomas, was implicated in the Babington plot,

and executed for high treason in 1586, being allowed to hang till he was dead.

(fn. 37)

Robert Charnock obtained a general pardon on the accession of James

I, but it is not known that he was a recusant. (fn. 38)

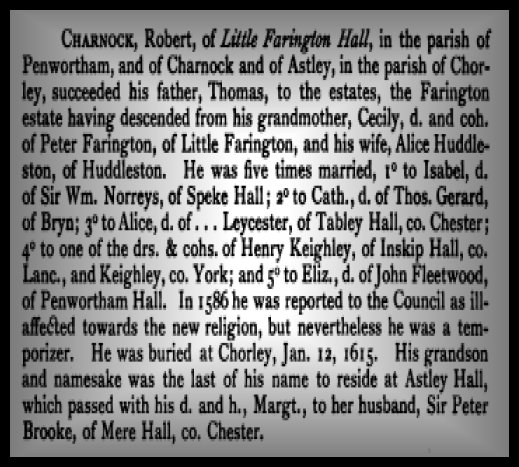

He married five times, and by his last marriage had a son and heir Thomas, who

married Bridget daughter and heir of John Molyneux of Barton-on-Irwell. A

pedigree was recorded in 1613, (fn. 39) when Robert, his son Thomas and grandson

Robert, aged nine, were all living. Robert Charnock died in 1616 holding the

manor as before, and leaving his son Thomas to succeed him. (fn. 40)

Thomas Charnock died in 1648; his son Robert, who had taken part in

the second defence of Lathom House in 1645, had his estates sequestered by

the Parliament, and was obliged to compound. (fn. 41)

He left a daughter and heir Margaret, who was living in 1732, having survived

both her husbands (1) Richard, younger son of Sir Peter Brooke of Mere, in

Cheshire, (fn. 42) and (2) John Gillibrand of Chorley. The moiety

of the manor of Charnock Richard descended with the issue of her first

marriage, and the late T. Townley-Parker of Cuerden was the representative of

the family. (fn. 43)

Other members of the Charnock family had lands in the township, (fn. 44)

and among the early owners occur the names of Garston, (fn. 45)

Fairhurst, (fn. 46) Wallhill, (fn. 47)

Wayward, (fn. 48) Molyneux, (fn. 49)

Hesketh, (fn. 50) Chorley, (fn. 51)

Orrell, (fn. 52) Dicconson (fn. 53)

and Anderton. (fn. 54)

The Hospitallers had land in Charnock Richard from an early time. (fn. 55)

The wives of Robert Charnock and of Edward Worthington were

landowners in 1542–3 (fn. 56) and the wife of Robert Charnock and John

Waring in 1564. (fn. 57) Jane Foster, widow, William Crichlow and

Elizabeth Parker, as recusants, asked to be allowed to compound for their

estates in 1653–4. (fn. 58) Several 'Papists' registered their estates

in 1717. (fn. 59) Robert Dalton (double assessed), Peter

Brooke and Thomas Lawe were the chief contributors to the land tax of 1783; in

1798 the names were—Mr. Dalton (sic), Mr. Parker's heirs and Mr. Low's

heirs. (fn. 60)

1628 -Recusants Roll

The Recusants Roll for Charnock Richard in the year 1628.

![]()

In connexion with the Church of England Christ Church was erected in 1860 (fn. 61) ; the patronage is vested in five trustees.

![]()

The Charnock family of Cuerden Hall Leyland Lancashire.

Muniments held at = Lancashire Record Office.

This catalogue of the Muniments at Cuerden Hall now

belonging to Reginald A. Tatton, Esqre, is divided into two parts, of which

Part I. comprises Nos. DDTA 1 - 186, and Part II. Nos. DDTA 187 - 584.

The contents of Part I have been placed in Green Cloth Boxes which themselves

are in Deed Case No. 3 The Deeds have been selected for their antiquity [the

earliest, No. 150, being of the time of Henry II, 1154-1189], or for their

intrinsic interest or for the seals attached to them. The first forty five

charters had already been arranged, numbered [and some photographed ], and

fastened into a vellum book labelled "Charnock Charters" with the

ostensible purpose of working out a pedigree of the Charnock family, as the

numerous modern notes show. These range from the late twelfth century to A.D.

1535 but the majority are of the 13th and 14th centuries. They are in fair,

though not strict chronological order and it has been thought best to leave

them as they are, and to number the rest of the Deeds onward.

They are therefore followed by other Charters relating in some measure to, or

containing some mention of, members of the family of Charnock.

From the early years of the fourteenthcentury the Cuerden estate was in the ownership of the Charnocks until sold to the Langtons, barons

of Newton-in-Makerfield, with whom it remained until another sale about 1605 to

Henry Banastre of Bank in Bretherton. From them it went, by the marriage of a

co-heiress, to Robert Parker of Extwistle. Another marriage brought in the

Brooke properties of Charnock Richard,

Astley in Chorley, etc. In 1906 the estates were bequeathed by Thomas

Townley-Parker to his nephew R. A. Tatton.

Contents:

A DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGUE OF MUNIMENTS.

The property with which the Deeds in the Vellum Book are concerned lies almost

exclusively in Charnock Richard, [from which

the family doubtless took its name] and Chorley, including Astley which is in

Chorley Parish and afterwards became the seat successively of the Brooke and Townley Parker

families. The rest of the Deeds besides others relating to the above mentioned

places, concern Burnley and Ightenhill, [the original home of the Parkers]

Clayton-le-Woods, Colne, Briercliffe and Extwistle [which manor was acquired by

the Parkers in the time of Henry VIII], Farington, Cuerden [the later home of

the Parkers], and other places in the neighbourhood in the County of Lancaster;

Meere, Rosthern, etc. in the County of Chester; Cowling, Glusburn, Cold Newton

or Bank Newton, Coniston, Gargrave, Sutton in Airedale, etc. in the County of

York.

Among the later-dated Deeds of Part I. are Royal Letters Patent, appointments

of various members of the families of Brooke, Parker and Townley as Sheriffs,

Deputy Lieutenants, and other Officials of the counties Palatine, Lancaster and

Chester. Many of these have attached to them excellent specimens of Royal Seals

for the County Palatine and the Duchy of Lancaster.

The arrangement of Part I is as follows: -

Box I. [Nos. 1-63] Co. Lancaster: Chorley and Astley, Coppull, etc.

Box II. [Nos. 64-86] Co. Lancaster: Bolton, Burnley and Ightenhill, Marsden,

Clayton-in-le-woods, Clitheroe, Colne and Trawden Chace, Croston and Maudesley,

Cuerden and Farington.

Box III. [Nos. 87-100] Co. Lancaster: Extwistle and Brierscliffe.

Box. IV. [Nos. 101-114] Co. Lancaster: Mellor, Tarleton, and Goosnargh,

Worthington and Worsthorn: - Co. Chester: Malpas, Mere and Rosthern,

Mouldsworth, Kelsall, Chester and Pickmere.

Box. V. [Nos. 115-152]. Co. York: Burnsall, Cooling, Craven, Flasby, Glusburn,

Newton-by-Gargrave, and Cold Coniston, Gargrave, Osgodby, Kirk Smeaton,

Sutton-in-Airedale, etc.

Box. VI. [Nos. 153-166] Personal and Miscellaneous. [including a General Pardon

by Henry VI. to John Banaster] etc.

Box. VII. [Nos. 167-186] Appointments, Warrants, Commissions, etc.

Part II. contains a few other selected charters which were found after Part I.

was arranged and a collection of later documents, the arrangement of which will

be found set out on the Contents Page of Part II. With one exception they

relate to places in the three counties mentioned above, and they include a

large number of Wills, Marriage Settlements, Inventories and similar documents.

Many expired Leases, mortgages, records of copyhold tenants, etc. of little

practical importance have not been particularly described, but arranged in

chronological order and made up into bundles.

An exhaustive index of places and names has been added.

![]()

The Charnock Family by Lord Burghley.

![]()

Residents of the Manor of Charnock Richard in 1588.

People and events in Charnock Richard 1199 to 1804 (a small selection of many).

Year 1199 - Ade de Charnock

Year 1215 - Richard de Charnock

Year 1216 - Richard de Charnock and the Knights of St. John.

Year 1300 - Richard de Charnock

Year 1421 - Henry de Charnock

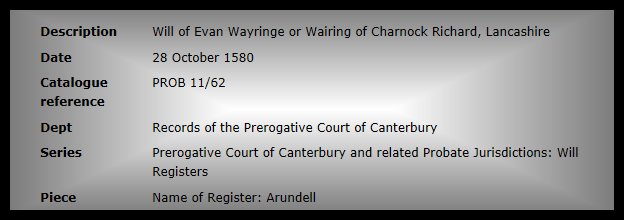

Year 1580 - Will of Evan Wairing.

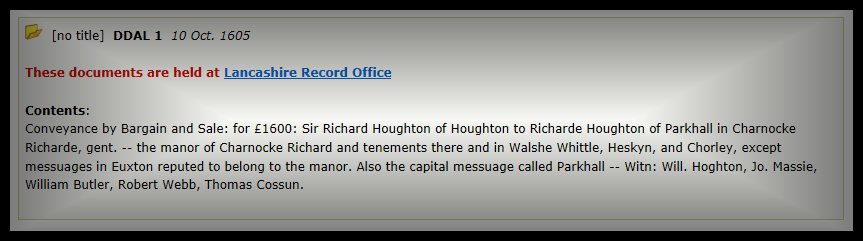

Year 1605 - Sale of the Manor of Charnock Richard.

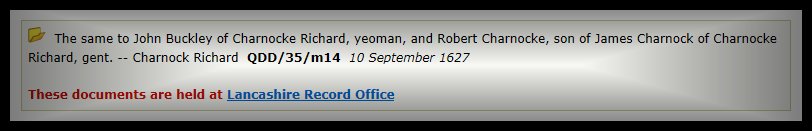

Year 1627 - James and Robert Charnock

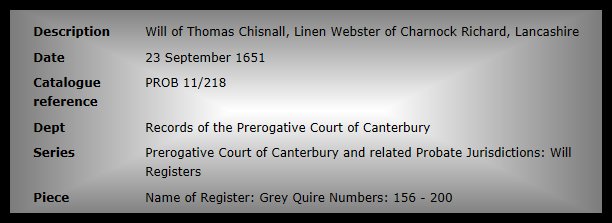

Year 1651 - Will of Thomas Chisnall.

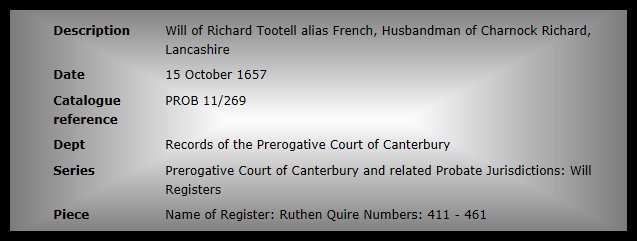

Year 1657 - Will of Richard Tootell.

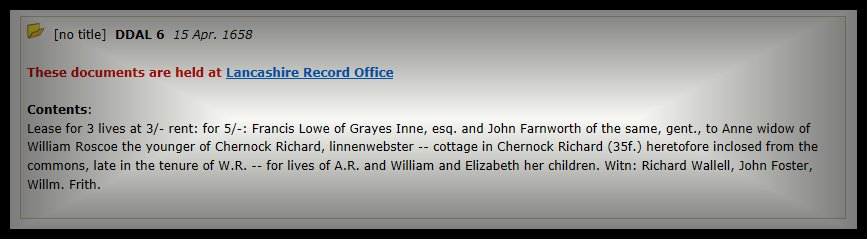

Year 1658 - John Farnworth solicitor to the Standish Family.

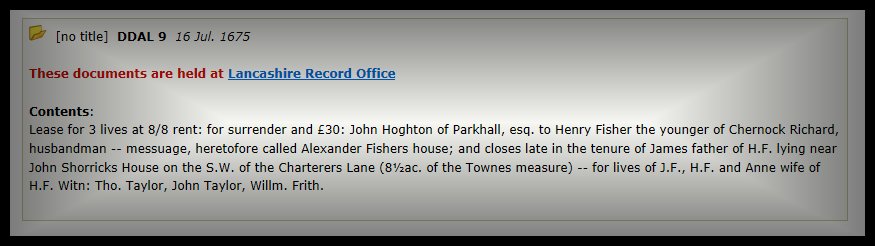

Year 1675 - Shorricks House.

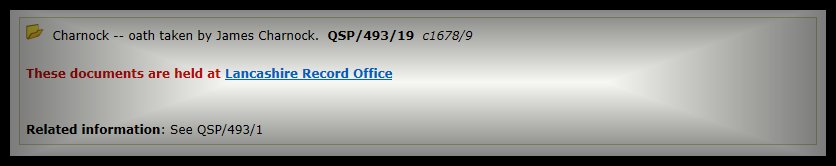

Year 1678 - Oath by James Charnock.

Year 1688 - Richard Armetryding - Charnock Richards - Butcher.

Year 1692 - James Charnock jr - High Constable.

Year 1714 - Lease of Park Hall - Charnock Richard.

Year 1736 - William Roscoe - Charnock Richards - Blacksmith.

Year 1741 - Bastardy.

Year 1755 - 1766 - 1769. "the Order of the Boot" kicked out of CHarnock Richard.

Year 1784 - Bastardy.

Year 1800 - Bastardy.

Year 1802 - Lease of Park Hall - Charnock Richard.

Year 1804 - Will of Elizabeth Charnock.

![]()

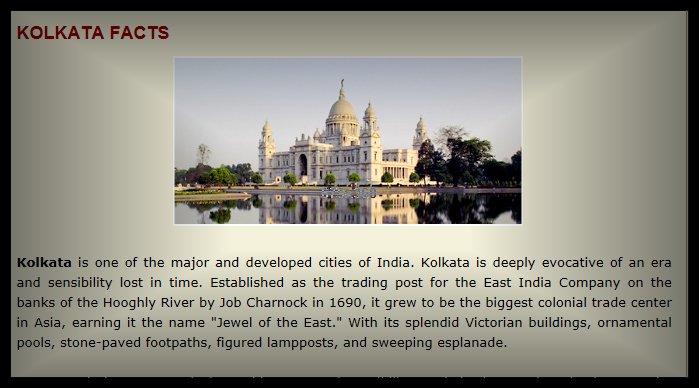

Job Charnock (c. 1630–1692) was a servant and administrator of the English East India

Company, traditionally regarded as the founder of the city of Calcutta.

Job Charnock

Charnock came from a Lancashire family from Charnock Richard and was the second son of Richard Charnock (d. c. 1665), of London. The Puritan preacher Stephen Charnock (1628–1680) was his elder brother. He went out to India on a private trading enterprise in the employ of the merchant Maurice Thomson, some time between 1650 and 1653, but in January 1658 he joined the East India Company's service in Bengal, where he was stationed by turn at Cossimbazar, Hooghly (a Portuguese trading settlement on the river of the same name), and Balasore. He learnt the local languages, cut his hair and dressed in "Moores fashion", and lived very much as an Indian among the Indians, who called him Channuck.

Charnock was described as a silent morose man, not popular among his contemporaries, but as "always a faithful man to the Company", which rated his services very highly. In addition to his business acumen, he won the Company's esteem by stamping out smuggling among his less scrupulous colleagues. His zeal in this regard made him enemies who throughout his life spread malicious gossip to discredit him.

Charnock was entrusted with the duty of procuring the Company's saltpetre and appointed to the centre of the trade, Patna in Bihar, on 2 February 1659. After four years at the factory he contemplated returning to England, but the court of directors in London were keen to retain his services, and won him over by promoting him to the position of chief factor in 1664.

About 1663 Charnock took a Hindu widow as his common-law wife. A Company servant, Alexander Hamilton, later wrote that she had been a sati and that Charnock, smitten by her beauty, had rescued her from her husband's funeral pyre by the Ganges in Bihar. She was said to be a fifteen-year-old Rajput princess. Charnock renamed her Maria, and soon after he was accused of converting to Hinduism. Though he remained a devout Christian, the story of his conversion and moral laxity was so widely believed that it became a cautionary tale in a more puritanical age.

Charnock was promoted to the rank of senior merchant by 1666, and became third in the Bengal hierarchy in 1676. He was now the Company's longest-serving servant in Bengal, and applied for a transfer to a more senior post. After some haggling due to difficulties with resentful colleagues who hoped to see him sent away to Madras, on 3 January 1679 the directors promoted him to the position of head at Cossimbazar, second in charge of the Company's operations in Bengal.

When Beard died on 28 August 1685 Charnock finally assumed the position of agent and chief in the bay of Bengal. By this time a crisis had arisen over restrictions on trade, and in particular the Mughal nawab's imposition of a customs duty of 3½ per cent, which the English refused to pay on the grounds that it was in breach of the original firman which exempted them from customs. Relations with the nawab deteriorated into violent conflict. When Charnock received word of his promotion Cossimbazar was under siege, and he could not leave to take up his responsibilities at Hooghly until April 1686. On his arrival he continued to resist what he saw as extortion, by force or persuasion, and when these did not serve, by taking the Company's business elsewhere.

Finding himself again besieged at Hooghly, Charnock put the Company's goods and servants on board his light vessels. Pursued by the nawab's troops, on 20 December 1686 he dropped down the river 27 miles (43 km) to Sutanuti, then "a low swampy village of scattered huts", but a place well chosen for the purpose of defence. From Sutanuti he moved on to Hijili in February 1687, where he was again besieged from March to June 1687. After negotiating a truce and safe passage, he transferred the factory back to Sutanuti in November 1687.

It was probably during this interlude at Sutanuti that Charnock suffered an irreparable personal loss in the death of his wife Maria. They had been together for some twenty-five years. They had one son (who would predecease his father), and three surviving daughters who were later baptised in Madras. Although Maria was buried like a Christian, and not cremated as a Hindu, Charnock was said to sacrifice a cock over her grave each year on the anniversary of her death, "after the Pagan Manner". The ritual resembles the Sufi custom of the panch peer or "five saints", which Charnock might have learnt from his years in Bihar. He was also said to have built his garden house at Barrackpore so as to be near her grave.

By 1686 the secret committee of the court of directors in London had decided the Company should establish a fortified settlement in Bengal, to resist what they regarded as arbitrary exactions and violent harassment by Mughal officials:

"we have no remedy left, But either to desert our Trade or we must draw that sword his Majesty hath intrusted us with to vindicate the Rights and Honour of the English Nation in India".

Accordingly in September 1688 the largest naval force the Company had ever assembled swept into the bay, with orders to blockade the ports and arrest the ships of the Grand Mughal, and, if this did not bring satisfaction, to take the town of Chittagong. Beard being dead, authority devolved to a reluctant Charnock as commander-in-chief. As he anticipated, Chittagong proved remote and unviable. Sutanuti had in the meantime been razed by the nawab's troops, therefore the squadron sailed for Madras, arriving on 7 March 1689.

In Madras Charnock persuaded the reluctant council, over the objections of its president, his old opponent William Hedges, that Sutanuti was the best place to establish the headquarters in Bengal, because of its defensible position and its deep-water anchorage for the fleet. The selection of the future capital of India was entirely due to his stubborn resolution.

In March 1690 the Company received permission from Aurangzeb in Delhi to re-establish a factory in Bengal, and on 24 August 1690 Charnock returned to set up his headquarters in the place he called Calcutta; the appointment of a new nawab ensured this agreement was honoured, and on 10 February 1691 an imperial grant was issued for the English to "contentedly continue their trade".

The directors showed their approval of Charnock's initiative by making his agency independent of Madras on 22 January 1692. Thereafter "Calcutta grew steadily till it became India's 'city of cities' and capital".

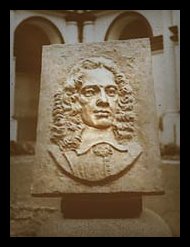

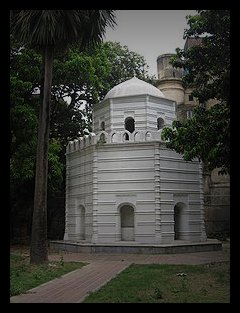

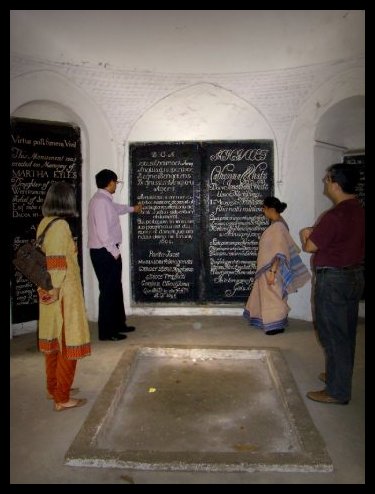

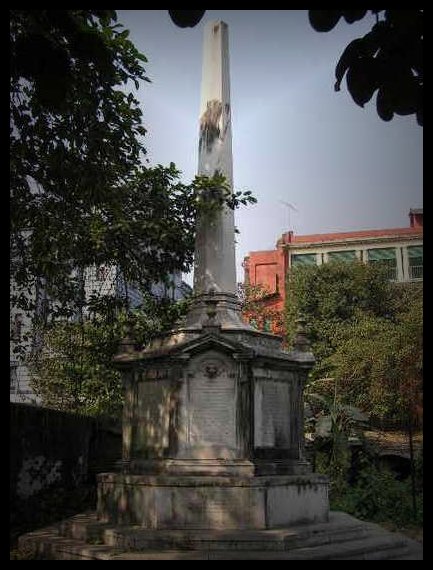

Job Charnock's Mausoleum.

St Johns Church - Calcutta - India the site of Job Charnock's Mausoleum.

Charnock died in Calcutta on 10 January 1692 (or 1693 according to an exhibition at the Victoria Memorial which points out that the 1692 date on his gravestone refers to an old calendar system by which the new year began in March), shortly after the death of his son. His three surviving daughters all remained in Calcutta: Mary (d. 19 Feb 1697), Elizabeth (d. August 1753), and Katherine (d. 21 Jan 1701); all found wealthy English husbands. Mary married the first president of Bengal,

Suszan Charnock - Calcutta - India.

A mausoleum was erected over Charnock's simple grave by Eyre, his son-in-law and successor, in 1695. It can still be seen in the graveyard of St. John's Church, the second oldest Protestant church in Calcutta after John Zacharias Kiernander's Old Mission Church (1770), and is now regarded as a national monument. His tomb is made from a kind of rock named after him as Charnockite.It is inscribed with the Latin

2.jpg)

D.O.M. Jobus Charnock, Armiger Anglus et nup. in hoc regno. Bengalensi dignissimum Anglorum Agens Mortalitatis suae exuvias sub hoc marmore deposuit, ut in spe beatae resurrectionis ad Christi judicis adventum obdormirent. Qui postquam in solo non suo peregrinatus esset diu reversus est domum suae aeternitatis decimo die 10th Januarii 1692. Pariter Jacet Maria, Iobi Primogenita, Carole Eyre Anglorum hicci Praefecti. Conjux charissima. Quae Obiit 19 die Februarii A.D. 1696–97.

Translation:

In the hands of God Almighty, Job Charnock, English knight and recently the most worthy agent of the English in this Kingdom of Bengal, left his mortal remains under this marble so that he might sleep in the hope of a blessed resurrection at the coming of Christ the Judge. After he had journeyed onto foreign soil he returned after a little while to his eternal home on the 10th day of January 1692. By his side lies Mary, first-born daughter of Job, and dearest wife of Charles Eyre, the English prefect in these parts. She died on 19 February AD 1696–7.

The inscription omits any mention of Charnock's Hindu wife Maria. Eyre may have hoped to make the public image of his predecessors and in-laws seem more respectable to the growing Anglican community in Calcutta. Even so, the monument was built by Bengali craftsmen, and its incorporation of Indo-Islamic design reflects the intersection of two cultures their union personified.

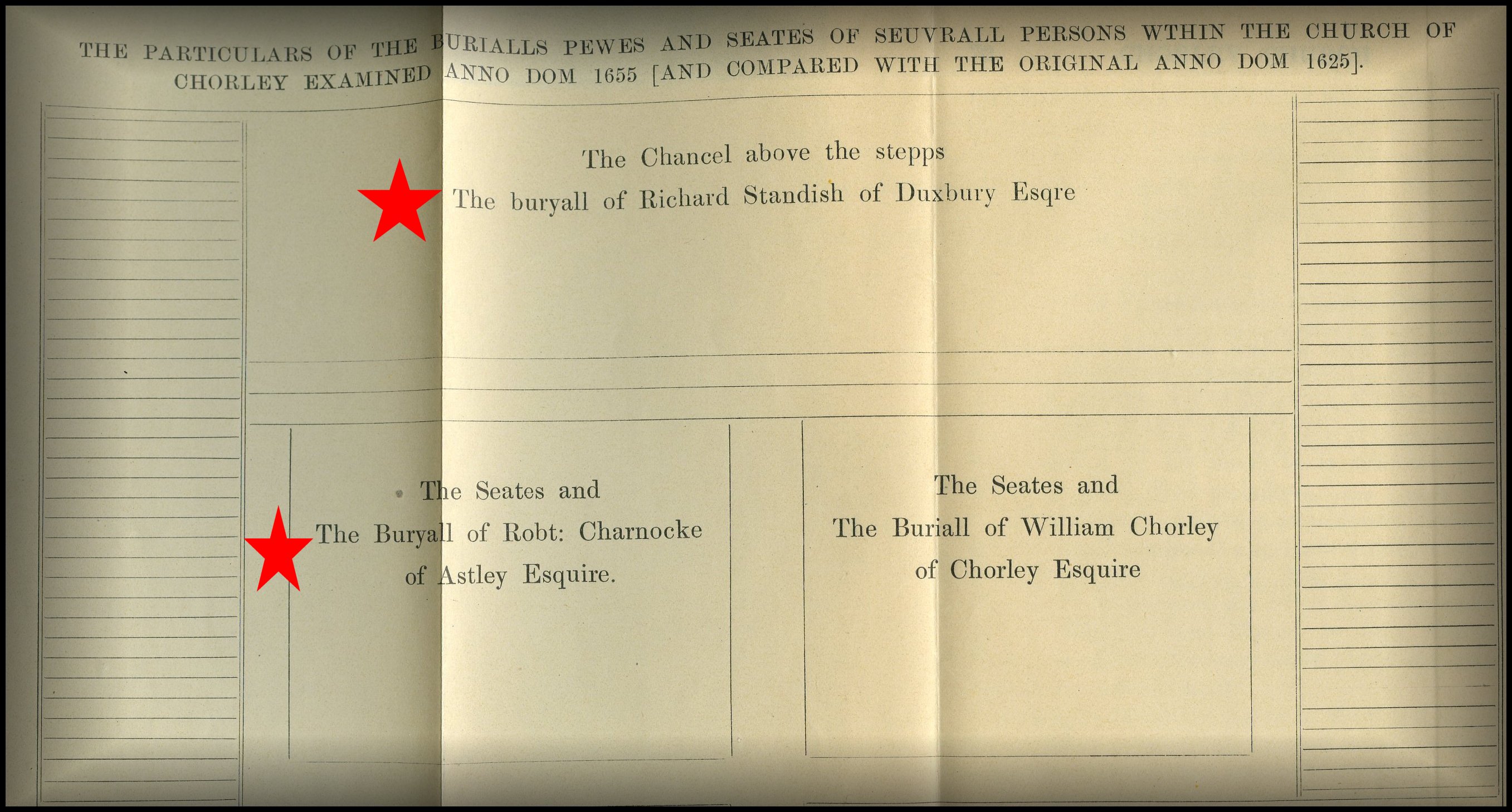

Job Charnock's ancestors are buried alongside the ancestors of Myles Standish in the Parish Church of St. Laurence Chorley Lancashire England.

Church of St. Laurence Chorley Lancashire England

Church of St. Laurence Chorley Lancashire England

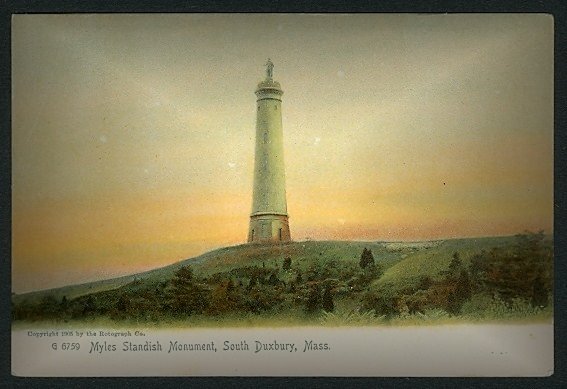

Job Charnock Myles Standish

Monument to Job Charnock Calcutta India Monument to Myles Standish Duxbury USA

Astley Hall Chorley Lancashire England the home of the Charnock family ancestors of Job Charnock.

![]()

Stephen Charnock, (1628–1680) (brother of Job Charnock.)

Dictionary of National Biography page 134. Stephen Charnock.

Charnock, Stephen

(1628–1680), nonconformist minister, was born in the

parish of St Katharine Cree, London, the son of Richard Charnock, attorney, who

traced his ancestry to Charnock Richard Lancashire. Admitted as a sizar at Emmanuel College,

Cambridge, on 30 May 1642, Charnock studied under William Sancroft. During

Charnock's Cambridge days ‘Evidences of the New-Birth appeared in him’ (S.

Charnock, A Treatise of Divine Providence, ed. E.

Veal and R. Adams, 1680, sig. A2v). He graduated BA (1646) and MA (1649). His

service as a household chaplain and his ministry in Southwark would have

occurred in the late 1640s. About 26 May 1649 he accepted a commission as

chaplain to Colonel Thomas Harrison's regiment of horse, and he was probably

present when it served in Wales from July 1649 until the summer of 1650. In the

latter year he became a fellow of New College, Oxford; he was incorporated MA

at Oxford on 19 November 1652, and appointed proctor in 1654.

While at Oxford, Charnock, along with Thomas Goodwin, Thankful Owen, and

Theophilus Gale, belonged to the gathered church that met at Magdalen College.

On 19 April 1655 Charnock wrote to Lord Wharton about the possibility of

obtaining the living at Winchendon, Buckinghamshire, but Charnock instead

accepted an invitation to go to Ireland, where Charles Fleetwood's

administration looked with favour on Independents (congregationalists). On 5

June the council of state asked Sir Gilbert Pickering and Colonel William

Sydenham to check Charnock's preaching certificate. By July he was in Dublin,

where Fleetwood and the council appointed him one of the ministers for a weekly

Monday lecture. When Thomas Wilkinson was transferred to St Catherine's,

Charnock took his place at St Werburgh's, and shortly thereafter he succeeded

Thomas Harrison at St John's, when Harrison was assigned to Christ Church on 8

September 1655. Occasionally Charnock preached at St Patrick's and St

Catherine's, and he helped examine ministerial candidates. Like that of most

other Independents in Ireland, his ministry was essentially confined to English

troops and civilian administrators. On 5 March 1656 Oliver Cromwell licensed

Charnock to keep his fellowship at Oxford notwithstanding his responsibilities

in Ireland, but three years later Henry Cromwell unsuccessfully sought

permission for Charnock to be appointed senior fellow at Trinity College, Dublin,

without resigning his fellowship at New College; the latter registered its

objection on 5 August 1659. Charnock was one of five ministers assigned to

examine a shipment of Quaker books confiscated when it arrived in Dublin in

1659. Charnock's income of £200 p.a. made him one of the ten highest-paid

clergy in Ireland in the late 1650s. In March 1660 he was one of eight

ministers commissioned by the convention which was meeting in Dublin to advise

it on religious matters, including clerical maintenance. On 9 March he and

Samuel Cox preached fast-day sermons, both of which the convention ordered

printed. (Two Sermons Preached at Christ-Church,

1660, is Cox's; Charnock's sermon was apparently not published.)

Charnock returned to London later in 1660. Having no ministerial appointment

for the next fifteen years he apparently supported himself by practising

medicine. About 1 April 1663 Charnock returned to Dublin, possibly for the

second time in that year, and there reportedly conferred with Thomas Blood,

Alexander Staples, and James Tanner, formerly clerk to Henry Cromwell's private

secretary. According to Tanner's subsequent confession Blood outlined plans to

seize Dublin Castle in May. Tanner also averred that Blood had previously shown

him a letter from Charnock in which Charnock said that if conditions were

‘ripe’ in Ireland, someone would shortly come to ‘seal the writings’; Tanner

interpreted this to mean Henry Cromwell (TNA: PRO, SP 63/313/187). Charnock

also allegedly asserted that dissidents in England were too constrained to act

until ‘the Eyce was broken’ in Ireland or Scotland, though they had supposedly

collected £20,000 to support their cause (TNA: PRO, SP 63/313/132). When the

government suppressed the conspiracy in May its agents failed to locate Charnock,

for whom an arrest warrant was formally issued on 19 June 1663. Tanner, Colonel

Edward Vernon, and the attorney Philip Alden, Vernon's agent, provided the

principal evidence against Charnock. Although the government learned that

Charnock had sometimes visited the stationer Robert Littlebury in London and

that he had ordered his correspondence sent to Littlebury, marked only with a

‘C’ for purposes of secrecy, Charnock used an alias (Clark) and eluded arrest.

It was probably at this time that he travelled in the Netherlands and France;

Littlebury admitted that Charnock had ‘an overture to go beyond seas’ (CSP dom., 1663–4, 177). Charnock was in London in

1666, for he lost his library in the great fire, but he apparently sought (or

at least received) no licence to preach under the declaration of indulgence in

1672.

An intensely private and studious man, according to his contemporary editors,

he emerged from the shadows in 1675 to become co-pastor, with the presbyterian

Thomas Watson, of a nonconformist congregation at Crosby Hall, Bishopsgate

Street, London. Although he preferred a congregational polity early in his

career, Charnock seems to have had no difficulty adjusting to the

presbyterianism of Restoration England. Indeed, Richard Baxter had recommended

him to Matthew Sylvester the previous year. In 1676 Charnock published the only

one of his works known to have appeared in his lifetime, The

Sinfulness and Cure of Thoughts, an exposition of Genesis

6: 5. He spent much of his last three years writing his magnum opus, Several Discourses upon the Existence and Attributes of God,

edited by Edward Veal (Veel) and Richard Adams and posthumously published in

1682. In it Charnock discussed ‘practical atheism’ and spiritual worship as

well as such divine attributes as immutability, omnipresence, infinite wisdom,

and omnipotency. Following his death in Whitechapel parish on 27 July 1680 he

was buried on 30 July at St Michael, Cornhill. John Johnson preached the

funeral sermon, published as The Shining Faith of the

Righteous (1680), in which he eulogized Charnock as ‘a powerful

Preacher, a good Casuist, [and] a judicious Divine’ (p. 40). He was also

honoured by the publication of New Poems upon the Death of …

Stephen Charnock (1680).

Although Charnock's contemporary editors also praised his preaching, less

educated listeners found him difficult to follow. In print his sermons tend to

be ponderous, and in his late years, as his eyesight failed, his oratory

diminished. Charnock knew Greek and Hebrew and was widely read, but he never

paraded his erudition in the body of his sermons. His reading included

classical authors such as Plato, Ovid, Pythagoras, and the Stoics; church

fathers such as Tertullian; the medieval philosophers Boethius and Averroes

(Ibn Rushd); Catholic writers such as Cajetan, Savonarola, and Suárez;

continental protestants such as Cocceius and Grotius; and English writers as

disparate as Cartwright, Baxter, Preston, Ames, Stillingfleet, Fuller,

Lightfoot, Davenant, and John Owen. His (new) library, auctioned in October

1680 for £366 5s. 1d., included approximately 1200 items. His

will, made on 25 July 1680, bequeathed £111, mostly to female relatives, and

the unspecified remainder to his executor and cousin, the widow Ann Sykes; the

will mentions neither wife nor children. Two of Charnock's works were published

later in 1680, A Sermon Preached … on 2 Cor. V. XIX,

calling for reconciliation with God and enmity toward sin, and A Treatise of Divine Providence, a substantive treatise

edited by Veal and Adams. The Sayings of … S. Charnock

also appeared in 1680. Veal and Adams produced a two-volume edition of his

works in 1684; the first volume, which sold very well, comprised Charnock's

treatise on divine attributes. The second included short works and sermons,

including a series of six on the Lord's supper, four on Christ's death, another

on 5 November discussing the theme of deliverance, and an exposition of 1 Timothy 2: 15 offering comfort to women during childbirth.

Two later editions of Charnock's works were published, the first, by Edward

Parsons, in nine volumes (1815–16), and the second, by James McCosh, in four

volumes (1864–5).

Richard L. Greaves.

![]()

|

1 |

1,946, including 14 of inland

water;Census Rep. 1901. |

|||

|

2 |

Including Bolton Green and

Charnock Green. |

|||

|

3 |

Subs. R. Lancs. bdle. 250, no. 9. |

|||

|

4 |

Lancs. Inq. and Extents (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), i, 29. |

|||

|

5 |

Ibid. 150. See also the account of

Shevington. |

|||

|

6 |

A number of charters relating to

this part of Charnock are in Kuerden MSS. iii, C 4. |

|||

|

7 |

Richard de Charnock, living in

1242, is the earliest member of the family known. |

|||

|

8 |

Lancs. Inq. and Extents, i, 270. |

|||

|

9 |

Charter R. 77 (12 Edw. I), m. 2,

no. 8. When William son of Henry was in 1292 summoned to show his right to

the market, fair and free warren the date of the fair was stated as St.

Botulph's day, &c.; Plac. de Quo Warr. (Rec. Com.), 369. |

|||

|

10 |

Richard the Demand released to

Henry de Lea all his right in the park which Henry had formed in Charnock;

and Adam son of Thomas de Thornton admitted that he had no right to break

down the park which Henry had formed with the leave of Thomas son of Richard

(de Charnock) his coparcener; Kuerden, loc. cit. no. 16, 28. |

|||

|

11 |

In 1422–3 Richard Hoghton demised

to Henry Bradshagh for twelve years the manor of Charnock Richard called Park

Hall; ibid. no. 58. Later, in 1443–4, Sir Richard Hoghton leased to Thomas

Riding land within the park of Charnock together with the mill; ibid. no. 59. |

|||

|

12 |

To a grant of land in Charnock to

William the Carpenter by Henry de Lea the latter's seal was appended; it

showed a bend fusilly; ibid. no. 7. Henry died in 1288, when it was found

that he had held the manor of Charnock with the park and 1½ oxgangs of land

of the heir of William de Ferrers (in demesne) and another oxgang in service,

rendering yearly 5s.; Inq. and Extents, i, 273. |

|||

|

13 |

Richard Hoghton was settled at

Park Hall as early as 1572, when Thomas Hoghton leased hall, water-mill,

&c., to him and his son Alexander for a hundred years; Duchy of Lanc.

Inq. p.m. xv, no. 39. |

|||

|

14 |

Lancs. Inq. p.m. (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), iii, 454, where is recited

a settlement on William Hoghton and Mary his wife, made in 1615. By this his

eldest son John (by the first wife) was made to rank after William and his

issue, he having roused his father's indignation by the hostility and malice

he had shown to his stepmother; Gillow, Bibl. Dict. of Engl. Cath.

iii, 329, 636. |

|||

|

15 |

See a preceding note and Gillow,

loc. cit. The Ven. Lawrence Johnson was chaplain at the hall about 1580, and

service seems to have been maintained there until 1751; ibid. iii, 330. |

|||

|

16 |

Ibid. |

|||

|

17 |

Royalist Comp. Papers (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), iii, 285–93, 303–4. Anne a

daughter of William Hoghton, a lunatic, had had her allowance stopped. John

Hoghton, elder brother of William, had had land leased to him in 1641, and

his daughter Margaret of Carr House was a petitioner in 1652, as was Margaret

the widow of William. Among the field names in the various deeds cited are

the Dear-bought and the Hold-back. |

|||

|

18 |

Ibid. iii, 290; Hugh Dicconson and

Robert Holt, the purchasers, were probably acting for John Hoghton. See also Index

of Royalists (Index Soc.), 42. |

|||

|

19 |

Dugdale, Visit. (Chet.

Soc.), 155. John married Elizabeth daughter and heir of Edward Ditchfield of

Ditton, with whom he had a share of that manor; see the account of Ditton. |

|||

|

20 |

Gillow, loc. sup. cit. |

|||

|

21 |

A settlement of the moiety of the

manor of Charnock Richard and other lands was made in 1663 by Dorothy

Ditchfield of Ditton, widow, John Hoghton and Elizabeth his wife; Pal. of

Lanc. Feet of F. bdle. 171, m. 99. The Park Hall estate was included in a

settlement made by Robert Dalton in 1753; ibid. bdle. 351, m. 191. An

indenture of the following year to which Robert Dalton and Elizabeth his wife

were parties is enrolled in the Com. Pleas D. Enr. East. 27 Geo. II, rot. 48,

93 d.; it concerns Charnock Richard, Welch Whittle, Euxton, Heskin and

Chorley. |

|||

|

22 |

Pal. of Lanc. Plea R. 645, m. 8.

The sale was completed in 1789. |

|||

|

23 |

Baines, Lancs. (ed. 1836),

iii, 521. |

|||

|

24 |

Ibid. (ed. 1870), ii, 167. |

|||

|

25 |

Information of Mr. Alison. |

|||

|

26 |

Lancs. Inq. and Extents, i, 149. He was living in 1252; ibid. 189. The Charnock

family has already been mentioned in the accounts of Astley in Chorley,

&c. |

|||

|

27 |

Thomas son of Richard de Charnock

shared the manor with Sir Henry de Lea; ibid. no. 5. Thomas de Charnock

attested various charters which may be dated about 1270. |

|||

|

28 |

Ibid. m. 13 d. They had obstructed

a road by which the rector had been accustomed to carry his corn, hay,

&c., to his house, and had to pay 6d. damages. |

|||

|

29 |

Norris D. (B.M.), no. 944. Adam

son of Henry de Charnock occurs as early as 1295; Final Conc. (Rec.

Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), i, 178. |

|||

|

30 |

Norris D. (B.M.), no. 573. In Dec.

1369 the Bishop of Lichfield granted Henry de Charnock a licence for his

oratory for two years; Lich. Epis. Reg. v, fol. 24. In 1370 Sir William de

Ferrers claimed land in Charnock against Agnes widow of Henry de Charnock and

Henry son of Adam de Charnock; De Banco R. 440, m. 56. Agnes widow of Henry

de Charnock was a plaintiff in 1376, a John del Bank being charged with waste

of her houses; ibid. 463, m. 6. |

|||

|

31 |

In 1427–8 in consequence of a

dispute as to the boundaries between Charnock Richard and Welch Whittle

Richard de Hoghton and Henry de Charnock agreed with Robert de Wrightington

as to a perambulation; Dep. Keeper's Rep. xxxiii, App. 30. |

|||

|

32 |

In Mar. 1498 Robert Charnock made

a feoffment of parts of his lands in Charnock, Chorley, &c., for the

benefit of his wife Margery; Add. MS. 32105, no. 758; Pal. of Lanc. Plea R.

85, m. 4. |

|||

|

33 |

Margery named in the last note

afterwards married Henry Banastre, and in May 1501 William Charnock and Henry

his son and heir became bound to the said Henry Banastre to abide an

arbitration; Add. MS. 32105, no. 743. William was the son and heir of Robert;

Pal. of Lanc. Writs Proton. 1 Aug. 16 Hen. VII. |

|||

|

34 |

Duchy of Lanc. Inq. p.m. viii, no.

28. In it is recited a settlement made by Robert Charnock grandfather of

Henry, in 1491, by which land in Speke called the Millfield was given to

Gilbert son of Robert with reversion to Thomas Charnock; other lands were to

the use of Robert himself and his wife Margery, with remainder to his right

heirs. William his son and heir succeeded and was followed by Henry, who

settled certain messuages in Speke, Charnock Richard and Chorley upon Cecily

daughter of Henry Farington for life. From the pedigree it appears that

Cecily married Robert Charnock, son of Henry; see also Visit. of 1533

(Chet. Soc.), 114. For suits by her in 1537 and 1540 see Ducatus Lanc.

(Rec. Com.), i, 156; ii, 62. |

|||

|

35 |

Visit. of 1567 (Chet. Soc.), 65. |

|||

|

36 |

Duchy of Lanc. Inq. p.m. xiii, no.

5. |

|||

|

37 |

Gillow, Bibl. Dict. of Engl.

Cath. i, 472. There is a graphic account of his execution in Hist.

MSS. Com. Rep. xiv, App. iv, 617. When he came to the ladder he began the

Ave Maria and asked all Catholics to pray for him, and again said the

Paternoster and Ave Maria. He confessed he had concealed the treason when he

knew of it, and begged the queen's pardon. He paid little attention to the

well-meant offices of the Protestant minister, and saying 'O Jesu, esto mihi

Jesus,' 'was thrown off the ladder . . . and so died fearfully and

obstinately in his religion. He had been a good soldier and a tall fellow. .

. He was a proper man in his apparel, somewhat tall and very strong, his

visage somewhat wan and pale.' |

|||

|

38 |

Gillow, loc. cit. |

|||

|

39 |

Visit. of 1613 (Chet. Soc.), 8; from the dates given it appears

to have been properly compiled from the family charters. Edward the eldest

son of Robert (by his first wife), who was living in 1567, was dead in 1613.

For the Molyneux marriage see the accounts of Barton and Bradford in

Manchester. |

|||

|

40 |

Lancs. Inq. p.m. (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), ii, 37–9. The settlement

made in 1585 is recited. |

|||

|

41 |

Royalist Comp. Papers, ii, 25. Captain Robert Charnock surrendered with the

Lathom garrison on 5 Dec. 1645, took the National Covenant and Negative oath,

and petitioned to compound in April 1647, his father being then alive, and

Robert having the mansion house of Astley in Chorley, a water-mill, &c.

His father had in 1644 made charges on his estate in favour of his daughters,

and died at Whitsuntide, 1648, his wife Bridget surviving him. The fine was

fixed at £260 in 1649. |

|||

|

42 |

The moiety of the manor of

Charnock Richard was held by Richard Brooke and Margaret his wife in 1672;

Pal. of Lanc. Feet of F. bdle. 188, m. 34. Henry Brooke of Astley, who died

in 1718, has a monument in Ormskirk Church; Trans. Hist. Soc. (new

ser.), xxii, 65. |

|||

|

43 |

The descent is thus given: Richard

Brooke -s. Thomas -s. Richard, s.p.-bro. Peter, who married Susannah Crookall

-s. Peter, d.s.p. 1787 -sister Susannah, who married T. Townley Parker. The

family has occurred at Bradford, near Manchester. Margaret Brooke, widow, and

Peter Brooke, esq., were vouchees in a recovery of the moiety of the manor in

1716; Pal. of Lanc. Plea R. 502, m. 4. See N. and Q. (Ser. 7), vi, 43. |

|||

|

44 |

Hastus de Charnock granted to

William son of Robert de Charnock land called Samsoncroft in Charnock at a

rent of 4d.; Thomas and Richard de Charnock were among the witnesses;

Kuerden MSS. iii, C 4, no. 19. |

|||

|

45 |

Henry de Gerstan gave his lands to

Sir Henry de Lea; Kuerden MSS. iii, C 4, no. 13, 15. Part of the land was

called Aldfield; ibid. no. 10. William de Lea gave to Henry de Gerstan for

his life 21 acres in Charnock with Fernisnape and Foxholes, Robfold and

Bakonliscroft; ibid. no. 31. Henry de Lea had given him land in Roulane;

ibid. no. 14. |

|||

|

46 |

The grant of Fairhurst has been

cited above. William le Estern gave it to John his son; ibid. no. 4. William

de Fairhurst was living about 1270; ibid. no. 5. He gave all he had in

Fairhurst to Sir Henry de Lea; ibid. no. 25. John de Fairhurst in 1283

demised to Sir William (Henry) de Lea for twelve years land in Charnock in

the field called Piladhalers and in the Holme in the same field, upon the

Yarrow; ibid. no. 18. |

|||

|

47 |

Adam de Fairhurst, with the

consent of Margery his wife, gave to Henry de Lea all the land which he had

with his wife by the gift of Robert de Wallhill, and Robert de Wallhill

confirmed this; ibid. no. 3, 6. It appears that Margery was Robert's

daughter; ibid. no. 22. |

|||

|

48 |

Thomas son of John Wayward gave

his brother John a fourth part of the mill of Charnock and all his share of

the mill croft; Kuerden MS. iii, C 7. Richard Wayward in 1313–14 claimed a

messuage, the fourth part of a watermill, &c., in 'Charnock' against

Thomas Wayward, but the jury decided that there was no town of Charnock

without addition, because there were both East Charnock and Charnock Richard;

Assize R. 424, m. 2 d. Adam son of Thomas Wayward was non-suited in 1324–5;

ibid. 426, m. 9. |

|||

|

49 |

The Molyneux family of Sefton held

land in the township, the tenure being variously stated at different times—of

the heirs of John Armetriding (1548), and lastly of Thomas Hoghton; see Duchy

of Lanc. Inq. p.m. ix, no. 2; xiii, no. 35. |

|||

|

50 |

Ibid. v, no. 16; the tenure was

unknown. |

|||

|

51 |

Ibid. vi, no. 17; held of Richard

Hoghton in socage. |

|||

|

52 |

William son of Henry de Orrell of

Newton and Cecily his mother in 1330 granted to Adam son of Thomas de Orrell

and Isabel daughter and heir of John son of Adam de Charnock and Margery

daughter of Henry de Orrell widow of John certain lands in Charnock for the

marriage of John brother of Adam; Kuerden MSS. iii, C 7. Nicholas Orrell in

1410 had lands in Charnock; Towneley MS. RR, no. 1554. |

|||

|

53 |

John Dicconson of the Row in

Eccleston, who died in 1639, held a messuage and land in Charnock Richard of

Thomas Charnock and William Hoghton by the rent of a steel spur; Duchy of

Lanc. Inq. p.m. xxviii, no. 71. |

|||

|

54 |

Hugh Anderton of Clayton in 1566

held land of Thomas Hoghton and Thomas Charnock by a rent of 3d.;

Duchy of Lanc. Inq. p.m. xi, no. 31. |

|||

|

55 |

It is mentioned in 1292; Plac.

de Quo Warr. (Rec. Com.), 375. The tenants about 1540 were: Thomas

Charnock paying a rent of 6d., William Orrell 18d. and 6d.,

Sir Richard Hoghton 12d., Richard Warin 4½d., Lawrence Wayward

9d.; Kuerden MSS. v, fol. 83b. Edward Standish of Standish in

1610 held land which had belonged to the Hospitallers;Lancs. Inq. p.m.

(Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), i, 190. |

|||

|

56 |

Subs. R. Lancs. bdle. 130, no.

126. |

|||

|

57 |

Ibid. bdle. 131, no. 210. |

|||

|

58 |

Cal. Com. for Comp. iv, 3175; v, 3186, 3194. |

|||

|

59 |

Engl. Cath. Non-jurors, 99, 128, 129. Their names were: Richard Parker, Robert

Foster, John Charnock, yeoman, William Fletcher, nailer, John Felton,

husbandman, and James Felton, linenweaver. |

|||

|

60 |

Land tax returns at Preston. |

|||

|

61 |

A district was assigned in 1861;Lond.

Gaz. 5 Feb. |

|||

![]()